Hey guys,

Over the past few weeks, I found myself engaging in thought-provoking conversations with some of the brightest minds at industry events in asset management from the night at Schroders to the night at the Luxembourg Fund event and many others. There’s one common theme that seems to reappear when discussing major macro changes, the deglobalisation of China and its detachment from US trade.

One of the events I attended was for all sorts of funds (PE funds, family offices, hedge funds etc) that are domiciled in Luxembourg; the total AuM of funds domiciled in Luxembourg totalled €5.2trillion. Yes, a lot of capital. I say that purely to emphasize the level of importance and attention some of the largest alternative asset managers place on this particular topic.

Everyone says follow the money, so in this report, we’ll be following those who have the best track record of doing so in this game.

Without further adieu, let’s break down the key macro themes surrounding US-China trade relations.

The Key Themes Across Macro Right Now

There are three key themes which are the pillars of this report.

Deglobalisation, demographics and diversification.

To rejig your memory, deglobalisation is the process of diminishing the interdependence and integration of economies around the world. In order to understand deglobalisation and the reason behind its resurgence, we must understand globalisation and the role it has played over the past three decades.

Chinese economic reform “Opening-up”

Globalisation promotes the connectivity and integration of the private and public sectors globally. US trade with China has grown tremendously when looking at the history of how China grew such large trade ties with the US to become the second largest economy globally. Since the late 80s, after a number of structural and economic reforms, China began normalising its relationship with the US in order to boost its global trade presence. Structural and economic reforms are changes to the way an economy operates. They’re designed to improve the efficiency, output and competitiveness of the economy; some economic reforms may be changes to monetary and fiscal policy whilst structural refers to the micro aspect of economics such as the jobs market.

China's reforms involved opening the country to foreign investment, allowing the private sector to flourish, and increasing overall transparency with the West. A key reform was lifting price controls, which reduced China's state subsidies, which cost the CCP over $6.6 billion annually.

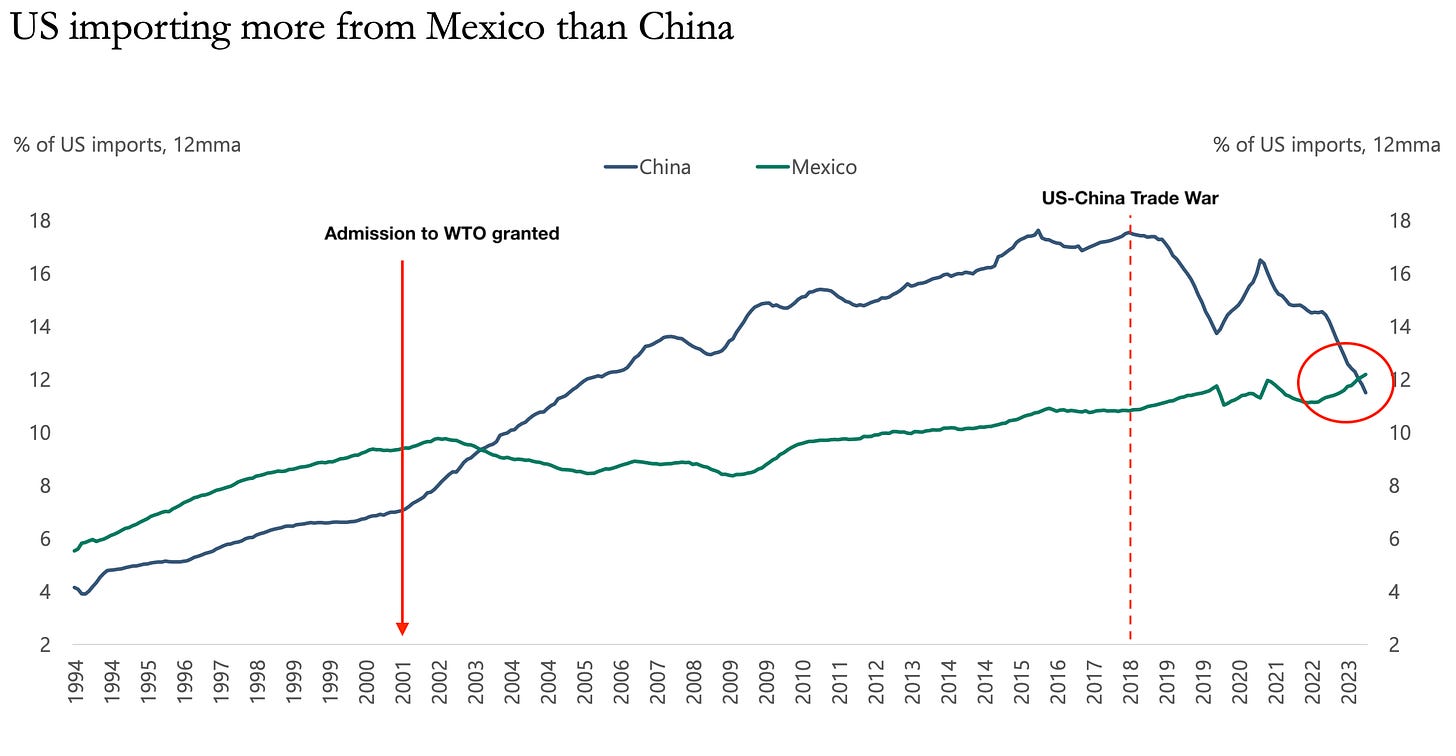

In 1986 China applied to the WTO (World Trade Organisation) under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, and was admitted in 2001. Prior to 2001, China's share of US imports was less than 7%. Admission to the WTO led to a significant increase in China's share of US imports, which reached over 10% by 2004. However, two decades later, we are seeing another major shift in the share of US imports from China.

Before we explore the shift, it’s vital to highlight the good that China’s economy has done not only for US trade, but world trade. The explosion in China’s share of US imports is a visual representation of globalisation. From 2001 to 2019 China’s globalisation effect helped keep inflation subdued because of the country’s cheap labour costs as its economy went through two decades of industrialisation. As a result, there was a massive global shift to offshore corporate supply chains to China, driven by the desire to reduce costs and improve production and quality in most cases.

The US-China trade war has been ongoing since January 2018, when President Trump imposed a number of tariffs and trade barriers on China with the goal of reducing the US trade deficit. From figure 2, you can see the immediate effect of the trade war and tariffs as the share of US imports from China declined to c.14% as of 2023.

For the global economy, 2020 was an eye-opener of the significant bottleneck risks posed by housing supply chains and manufacturing units in China. The crisis forced many companies to re-wire their supply chain dynamics.

This is where diversification comes in.

The supply shock of COVID-19 simply accelerated the diversification and movement of supply chains away from China. Companies globally have begun setting up manufacturers and supply chains in countries like Vietnam, which is expected to attract both a lot of FDI (foreign direct investment) and attention from giant conglomerates. Apple is among the names to relocate 11 manufacturing units to Vietnam, enhancing its supply chain strategy.

Although it appears Mexico is replacing China as the largest trading partner with the US, that is not the case. Through the diversification of company supply chains, US direct trade may be greater with Mexico, but those goods are still coming from China. So Chinese goods are still making their way to us in the West, now it’s just through third parties such as Mexico.

Now, to bring these high-level macro and regime shifts down to our level, financial markets, the question in your mind should be “What’s the effect on markets?”. Simple, if companies are shifting supply chains, and reshoring out of China that means there’s a net capital outflow from Chinese markets, which can be seen in weak fixed-income demand and equity markets performance.

YTD the SSE is down 2.03%, struggling to attract optimism even in the midst of large stimulus and liquidity injections from the PBOC.

The yield differential between CN10Y and US10Y has played a crucial role in the depreciation of the onshore and offshore Yuan.

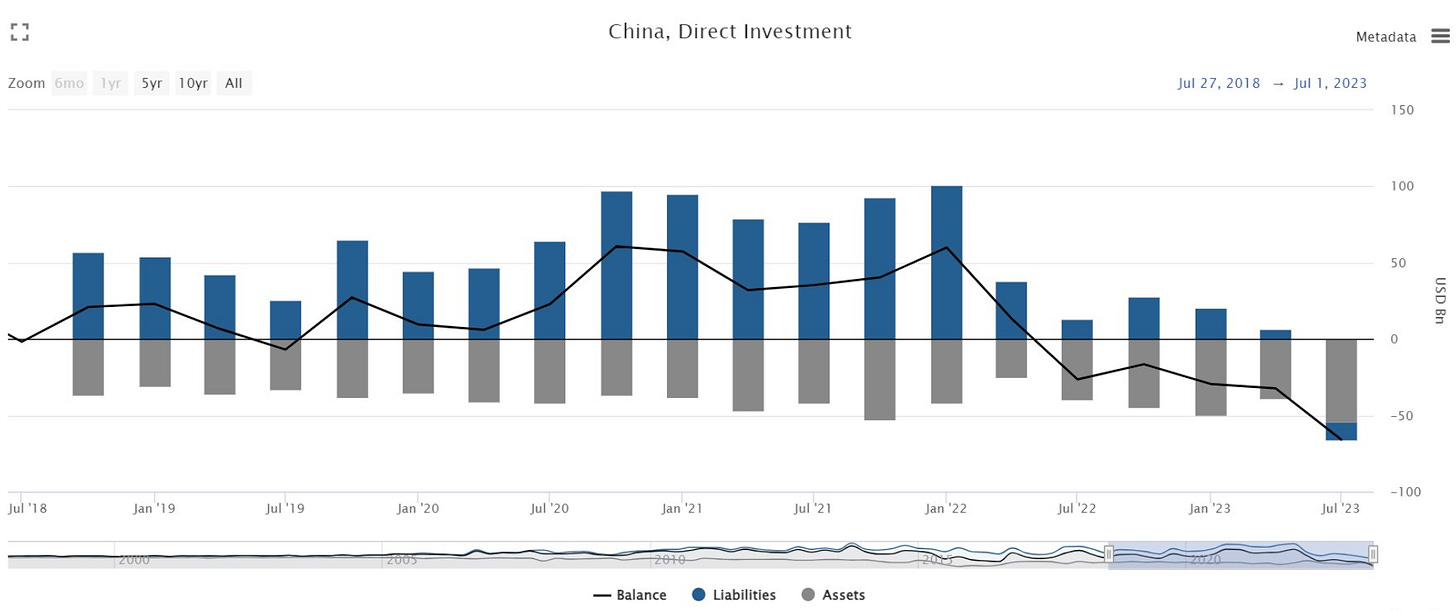

FDI data from the mainland has also disappointed as seen by the chart below.

As a rule of thumb, the liabilities (blue bar) represent the total value of foreign direct investment that China has received from foreign investors, and the assets (grey bar) represent the total value of Chinese direct investment abroad. Through the July-September ‘23 period, China recorded its first deficit of foreign investment. The observed outflows could be attributed to the weak economic conditions and the lack of incentive to invest in mainland China, given that risk-free yields at 5% make it difficult for EM IG to provide an attractive risk premium for investors.

China’s economy may well be going through a cyclical period of low growth, low rates and low consumer demand but the large macro shift observed from 2018 is largely at play with producers rethinking their exposure to Chinese dynamics and markets. These factors bring to thought potential opportunities and ideas both investors and speculators could explore within the markets. CNH shorts remain a trade idea I’ve explored with you all in the past quarter, as yield differentials remain a relevant factor. However, with the Fed nearing the end of its hiking cycle, there is a concern that the trade may no longer have the potential to generate alpha. So I’ll be observing developments closely across mainland China to keep you updated.

As always, I appreciate your readership MMH subscribers.